Understanding Gold Geology in Western Australia: Where and Why Gold Forms

Learn about the geological processes that created WA's goldfields and how understanding gold formation patterns can help you find more nuggets.

Understanding Gold Geology in Western Australia: Where and Why Gold Forms

For the prospector, understanding basic gold geology transforms metal detecting from random searching into strategic hunting. Western Australia’s goldfields didn’t form by accident—they’re the result of specific geological processes that occurred over billions of years. By learning to recognize the signs and structures that indicate gold-bearing areas, you can dramatically improve your success rate and spend more time detecting productive ground instead of barren areas.

The Deep Time Origins of WA’s Gold

Western Australia’s gold deposits are ancient beyond comprehension. Most formed during the Archean Eon, between 2.7 and 2.6 billion years ago, making them among the oldest gold deposits on Earth.

The Yilgarn Craton

The foundation of Western Australia’s goldfields is the Yilgarn Craton, a massive shield of ancient rock that forms the core of the southwestern portion of the continent. This stable piece of Earth’s crust has remained largely unchanged for billions of years, preserving the geological structures and mineral deposits within it.

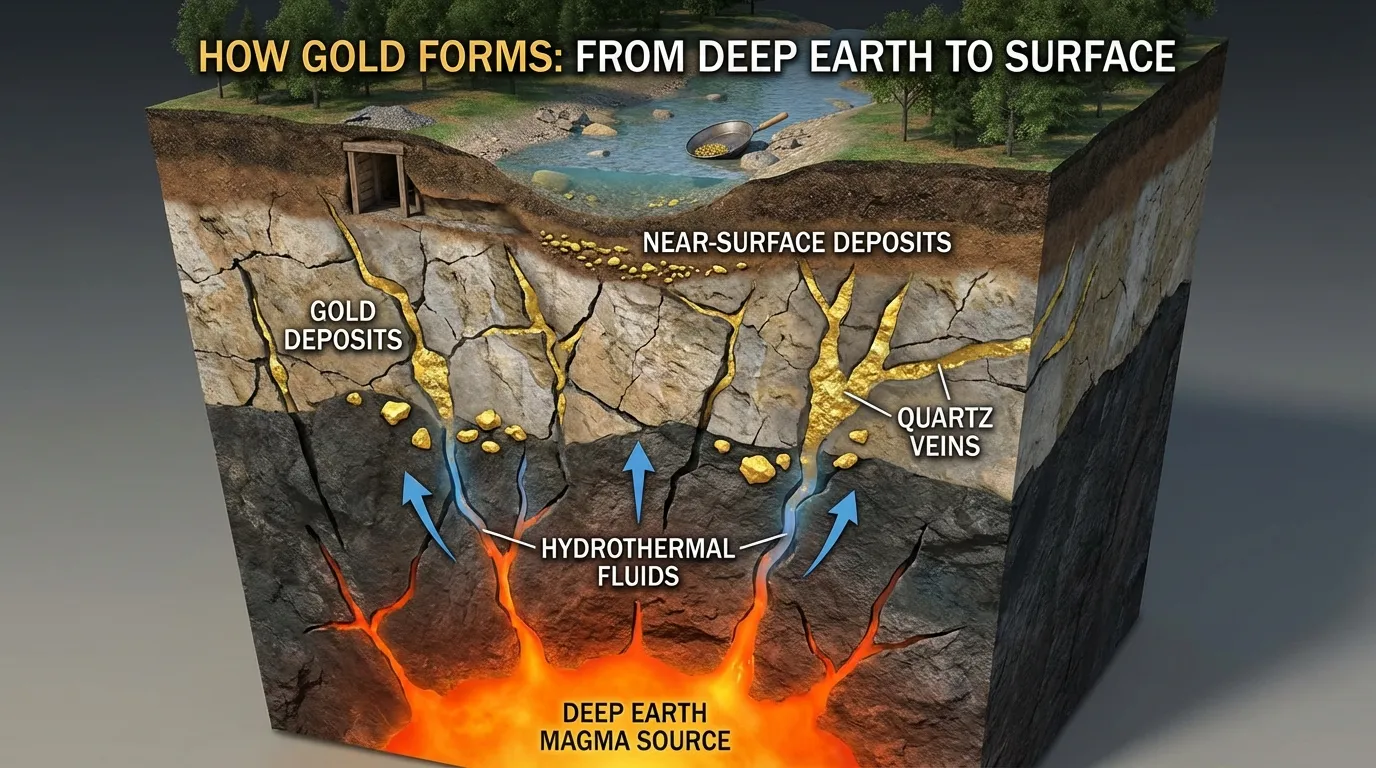

During the Archean period, the Yilgarn Craton was the site of intense volcanic activity and mountain-building events. Deep below the surface, superheated fluids carrying dissolved gold and other minerals rose through cracks and fissures in the rock. As these fluids cooled and the chemistry changed, the gold precipitated out of solution, forming concentrated deposits along these pathways.

Greenstone Belts

The primary gold-bearing structures in Western Australia are found within “greenstone belts”—elongated regions of volcanic and sedimentary rocks that have been metamorphosed (changed by heat and pressure). These belts contain the mineral assemblages that indicate gold potential.

The major greenstone belts in WA include:

- The Kalgoorlie-Kambald a-Norseman belt

- The Murchison Province belts

- The Eastern Goldfields Province belts

These greenstone belts are where the majority of WA’s gold has been found, both historically and in modern times.

Primary vs. Secondary Gold Deposits

Understanding the difference between primary and secondary gold is crucial for prospectors.

Primary Gold: Gold in Bedrock

Primary gold deposits are where gold originally formed in the bedrock. This gold is typically found in quartz veins or disseminated through the host rock. In its primary state, gold is often:

- Associated with quartz veins (white or milky quartz)

- Found in mineralized zones within specific rock types

- Present as fine gold within the rock matrix

- Sometimes visible as gold-bearing quartz specimens

Most of Western Australia’s major gold mines extract primary gold from underground reefs or large open pits. For detectorists, primary gold in bedrock is generally too deep to detect with standard equipment, but exposed outcrops can sometimes be worth investigating.

Secondary (Alluvial/Eluvial) Gold: Gold in Soil

Secondary gold is what most detectorists target. This is gold that has been weathered out of the primary source rocks and redistributed by natural processes. Secondary gold comes in two main types:

Eluvial Gold: This gold has weathered out of nearby bedrock but hasn’t traveled far. It’s found in soil directly above or adjacent to the source. Eluvial gold tends to be:

- Angular or rough in shape (hasn’t been tumbled)

- Larger than alluvial gold on average

- Found near the source reef or deposit

- Often the first type found in new goldfield areas

Alluvial Gold: This gold has been transported by water from its source, sometimes considerable distances. Alluvial gold is typically:

- Smoother and more rounded (water-worn)

- Found in ancient and modern creek beds

- Concentrated in low points and behind obstacles

- Smaller on average (larger pieces settle out first)

The vast majority of nuggets found by detectorists in WA are eluvial gold—pieces that have weathered out of nearby sources and remain relatively close to where they originated.

Reading Indicator Rocks and Minerals

Certain rocks and minerals indicate increased gold potential. Learning to recognize these can help you identify promising areas.

Quartz: Gold’s Frequent Companion

Quartz and gold have an intimate relationship. The majority of primary gold in WA is associated with quartz veins. For prospectors, this means:

White/Milky Quartz: Large quartz veins, especially those showing evidence of mineralization (staining, other minerals present), are excellent indicators. Old-timers specifically targeted quartz reefs because they knew gold was commonly present.

Quartz Float: Pieces of quartz scattered on the surface, especially if they show iron staining or other mineralization, indicate a nearby quartz reef source. Following quartz float “uphill” can lead you to the source reef.

Specimen Quartz: Occasionally you’ll find quartz with visible gold inclusions. These specimens are valuable both for their gold content and as collector pieces. More importantly, they indicate you’re in a productive area.

Ironstone and Laterite

Much of Western Australia’s surface is covered with laterite, a reddish-brown layer formed by intense weathering of the underlying rocks. Within this laterite:

Ironstone: Hard, iron-rich rocks (often red, brown, or black) can be excellent indicators. Gold often accumulated at the interface between weathered rock and iron-rich zones. Ironstone ridges and outcrops are prime detecting targets.

Ferruginous Zones: Areas with significant iron staining (red, orange, or brown coloration) indicate water flow and chemical activity—processes that can concentrate gold.

Pisoliths: These small, round iron-rich nodules are common in laterite profiles. While not directly indicating gold, areas where pisoliths are present often have the right geological setting for gold accumulation.

Greenstone

Despite being weathered and often covered, greenstone rocks sometimes outcrop at the surface. These ancient volcanic rocks are the host for much of WA’s gold. If you find greenstone outcrops, you’re in historically productive rock types.

Geological Structures That Concentrate Gold

Understanding how geological structures control gold distribution helps you target the right areas.

Old Workings: The Best Indicator

The most reliable “geological indicator” is evidence of old mining activity. Wherever the old-timers dug, they found gold. Their simple tools meant they couldn’t extract all the gold, and erosion since then has exposed more. Look for:

- Shallow shafts and pits

- Mullock heaps (waste rock piles)

- Stone arrangements and ruins

- Trenches along quartz reefs

- Flattened areas where dry-blowers operated

Detecting around these old workings is often highly productive. Modern detectors can find gold the old-timers missed.

Gullies and Water Courses

Water is one of nature’s best gold concentrators. Ancient and modern water courses can contain significant gold.

Ancient Creeks: Many of today’s gullies and creek beds are much older than they appear. Some represent drainage systems that were active millions of years ago when WA was wetter. These paleo-channels can be richly gold-bearing.

Modern Ephemeral Creeks: Even though they rarely flow, these watercourses concentrate gold during occasional flood events. Focus on:

- Inside bends where water slows

- Behind large rocks and obstacles

- In cracks and crevices in bedrock

- At the junction of gullies

- In deeper holes and depressions

Ridges and High Ground

While water concentrates gold in low areas, ridges and high ground can also be productive:

Quartz Reefs: These resistant ridges often stand out because the surrounding rock has eroded away. Detecting along the sides of quartz ridges, where gold has weathered out and moved downslope, can be very productive.

Ironstone Ridges: Similar to quartz reefs, these resistant features can harbor gold both within them and in the soil around them.

Elevated Flats: Flat areas on ridges sometimes represent ancient land surfaces preserved from erosion. These can contain eluvial gold that’s been in place for millions of years.

The Golden Triangle: Understanding “Gold Traps”

Gold, being heavy (about 19 times denser than water), behaves predictably when moved by water or gravity. Understanding gold physics helps you predict where nuggets might accumulate.

Gravity Traps

On slopes, gold moves downward over time through a process called “soil creep.” This happens incredibly slowly, but over thousands of years, gold can migrate substantial distances. Look for:

Changes in Slope: Where steep slopes flatten out, gold accumulation can occur.

Obstacles: Large rocks, fallen logs, and other obstacles trap downward-moving gold. Detecting on the downhill side of obstacles is often productive.

Depressions: Small bowls and depressions trap gold moving downslope. These subtle features are easy to miss but can be gold-rich.

Water Traps

When water flows (even rarely), it moves gold until the water slows enough for gold to settle:

Inside Bends: Water flows faster on the outside of bends, and slower on the inside. Gold deposits where water slows.

Behind Obstacles: Rocks, logs, and even vegetation create slack water zones where gold settles.

Bedrock Cracks: When gold reaches bedrock, it works into cracks and crevices where it’s protected from further movement. If you can detect exposed bedrock, pay special attention to these natural gold traps.

Confluence Points: Where two gullies meet, gold accumulates. These junctions are always worth thorough investigation.

Hot Rocks and Mineralization

One challenge in WA’s goldfields is “hot rocks”—naturally magnetic rocks that trigger your detector despite containing no gold. Understanding these helps reduce frustration.

What Are Hot Rocks?

Hot rocks are typically ironstone pieces or other rocks with high magnetic susceptibility. They’re the result of the same mineralization processes that brought gold to the area, so ironically, areas with lots of hot rocks often have gold potential.

Managing Hot Rocks

Rather than viewing hot rocks as pure annoyance:

- Consider them indicators that you’re in mineralized ground

- Learn your detector’s hot rock signals (they often sound different from gold)

- Use discrimination features cautiously (you might reject small gold along with hot rocks)

- Accept that digging hot rocks is part of the process in productive areas

Practical Application: Reading Ground in the Field

Applying geological knowledge in the field transforms prospecting from wandering to strategic searching.

Site Selection Strategy

-

Research First: Study geological maps, mining history, and old reports before heading out. The Geological Survey of Western Australia provides excellent resources.

-

Look for Multiple Indicators: The best sites show several positive signs:

- Evidence of old workings

- Quartz or ironstone present

- Appropriate rock types (greenstone belts)

- Topographical features that could concentrate gold

- Historical gold production in the area

-

Start at Known Producers: Begin at areas with documented gold finds, then expand outward based on geological understanding.

Sample and Test

When you arrive at a new location:

-

Detect Known Targets: If there are old workings, start there to confirm your detector is working properly and the area has gold potential.

-

Sample Broadly: Don’t spend all day in one spot initially. Test various features—a quartz ridge, a gully, flat areas—to identify which is most productive.

-

Expand on Success: When you find gold, carefully note the exact location and geological context. Search the immediate area thoroughly, then apply what you learned to similar geological settings nearby.

Advanced Concepts: Oxidation Zones and Supergene Enrichment

As you develop your understanding, more complex concepts become relevant.

The Oxidized Zone

Near the surface, oxygen-rich groundwater reacts with sulfide minerals in gold-bearing rocks, creating an oxidized zone. This oxidation process can:

- Free gold from its original mineral associations

- Create secondary gold enrichment at the oxidation boundary

- Produce distinctive orange/brown iron staining

- Extend from surface to depths of 30-100 meters typically

Most nugget detecting occurs in this oxidized zone.

Supergene Enrichment

In some areas, downward-percolating groundwater dissolved fine gold from upper levels and redeposited it lower in the profile, creating zones of enrichment above the water table. These zones can have much higher gold grades than the original primary deposit.

For detectorists, understanding supergene enrichment explains why some areas at specific depths or horizons are more productive than others.

Regional Variations in WA Geology

Different goldfield regions have distinct geological characteristics.

Eastern Goldfields (Kalgoorlie-Norseman)

- Dominated by the Archaean greenstone belts

- Major structural corridors (like the Keith-Kilkenny Fault)

- Deep laterite profiles

- Extensive quartz veining

- Multiple generations of gold mineralisation

Murchison Province

- Older greenstone belts (2.7+ billion years)

- Generally smaller deposits but numerous

- Extensive ironstone and laterite cover

- Historical alluvial gold production

- Good nugget-detecting territory

Ashburton-Pilbara Region

- Younger geology (Proterozoic)

- Different gold-forming processes

- Conglomerate-hosted gold (Nullagine, Marble Bar)

- Less deeply weathered than southern goldfields

- Unique prospecting challenges and opportunities

Conclusion: Geology as Your Guide

Understanding gold geology doesn’t require a degree in earth sciences, but learning the fundamentals dramatically improves your prospecting success. When you understand why gold is where it is, you can:

- Eliminate unproductive areas before you start detecting

- Recognize promising features that others might overlook

- Make better decisions about where to spend your limited detecting time

- Understand why some finds cluster while other areas are barren

- Predict where else gold might occur based on successful finds

Western Australia’s goldfields have produced thousands of tonnes of gold over more than 130 years, yet new significant finds continue to be made. The gold is still out there—billions of years in the making, waiting in the ancient rocks and soils of the Yilgarn Craton.

By thinking like a geologist while detecting, by reading the rocks and landforms, and by understanding the deep-time processes that concentrated gold in specific places, you transform yourself from someone randomly swinging a detector into a strategic prospector with genuine insight into where the next nugget lies.

The ground has stories to tell, written in stone over unimaginable time spans. Learn to read these stories, and the goldfields will reward you with more than just nuggets—they’ll reward you with the profound satisfaction of understanding one of Earth’s most fascinating geological phenomena.